It is no secret that farming is a difficult enterprise. Present economic and political conditions have made it even more challenging, particularly in the dairy industry. The pastoral vision of agriculture—much of it based on Jefferson’s agrarian ideals of being a wholesome, noble act performed by people who are the salt of the earth—largely remains the image shown to the public, and perhaps sometimes is what we believe it to be ourselves. Still, while maybe indeed noble, farming is not exempt from the maladies of contemporary society. Farming can be a hardship, but for some has been made even more difficult.

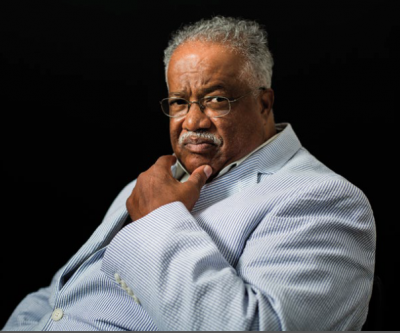

It has been several years since Ralph Paige has passed away at the age of 74. His biography published across all news outlets both honored his commitment to fight for the equality of the black farmer, highlighted the historical difficulties faced by African-Americans in agriculture, and remind us of the work that is yet to be done.

As can be imagined, black farmers faced rigorous discrimination after the Civil War. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave away 270 million acres of US land, but because of bureaucratic prejudice, relatively little of it made it into the hands of African-Americans. In 1865 the Freedman’s Bureau was created by Lincoln to help support the transition of the recently liberated slave population into society. Nonetheless, despite such efforts, blacks did not receive their “40 acres and a mule” promised to them by General Sherman, but instead were given smaller allotments of 10 to 15 acres. Whites received the lion’s share of financial subsidies, and the introduction of Jim Crow laws further reduced land ownership by African-Americans, let alone the possibility to thrive on it.

There are few who read this that would have been unaware or surprised by the injustice faced by black farmers in the 19th century. What is unnerving to discover, however, is how the legacy of such discrimination persists.

Representation for and by black farmers, particularly in the south, became one of the many vehicles used by the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s to work towards greater equality. They were opposed by a formidable adversary: the United States Department of Agriculture. Pete Daniel, in his book Dispossession: Discrimination against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights, traces the tactics employed by the USDA to deter, intimidate, and sometimes force black farmers off their land. According to Daniel, “When SNCC in the mid-1960s organized African American farmers to vote in ASCS elections, county offices issued inaccurate maps, neglected to send black women ballots, manipulated ballots to confuse black farmers, all with the complicity of the Washington USDA office. There was also violence, intimidation, and economic retaliation.” The USDA was not composed of people who were the salt of the earth.

In response to the discrimination originating from both individuals and the US government, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives was established. Ralph Paige was an active member of the organization for 46 years, the last 30 of which he was its acting leader. The Federation was the first major attempt to organize black farmers into cooperatives and educate them on the legal means to retain their land, including drafting wills. The Federation allowed African-American farmers to become increasingly independent from outside institutions that were biased and sometimes vulturine.

Most famously, in 1992 Paige organized the “Caravan to Washington” to protest the funds that were to be issued by congress through the Minority Farmers Rights Acts, but that were not actually appropriated. In addition to the Washington rally, Paige was instrumental in helping black farmers bring, at that time, the largest class action suit against the USDA in 1997. In Pigford vs. Glickman, Pigford, a black farmer from South Carolina, asserted that he was forced to foreclose because of the discriminatory practices of the agency. Pigford won, eventually attaining over a billion dollars for black farmers across the country and forcing the United States government to address significant inconsistencies in its practices. The lawsuit encouraged other minorities, including females, Latinos, and Native American farmers, to seek justice from the USDA.

Since the implementation of the Jim Crow laws, black agricultural holdings have undergone a steady decline. In 2012, there was estimated to be a little over 33,000 farms whose principal operator was African-American. The work started by Ralph Paige is not yet complete. As we pay tribute to a man who fought for the equality of a group of people that has been the object of prejudice, it is important to recognize the difficulties faced by minorities in agriculture, and continue to seek ways to work towards greater equality.

This article is part of The Milk House Column series, published in print across three countries and two languages. It can also be found at themilkhouse.org.

This article appeared in a similar form in Progressive Dairyman.