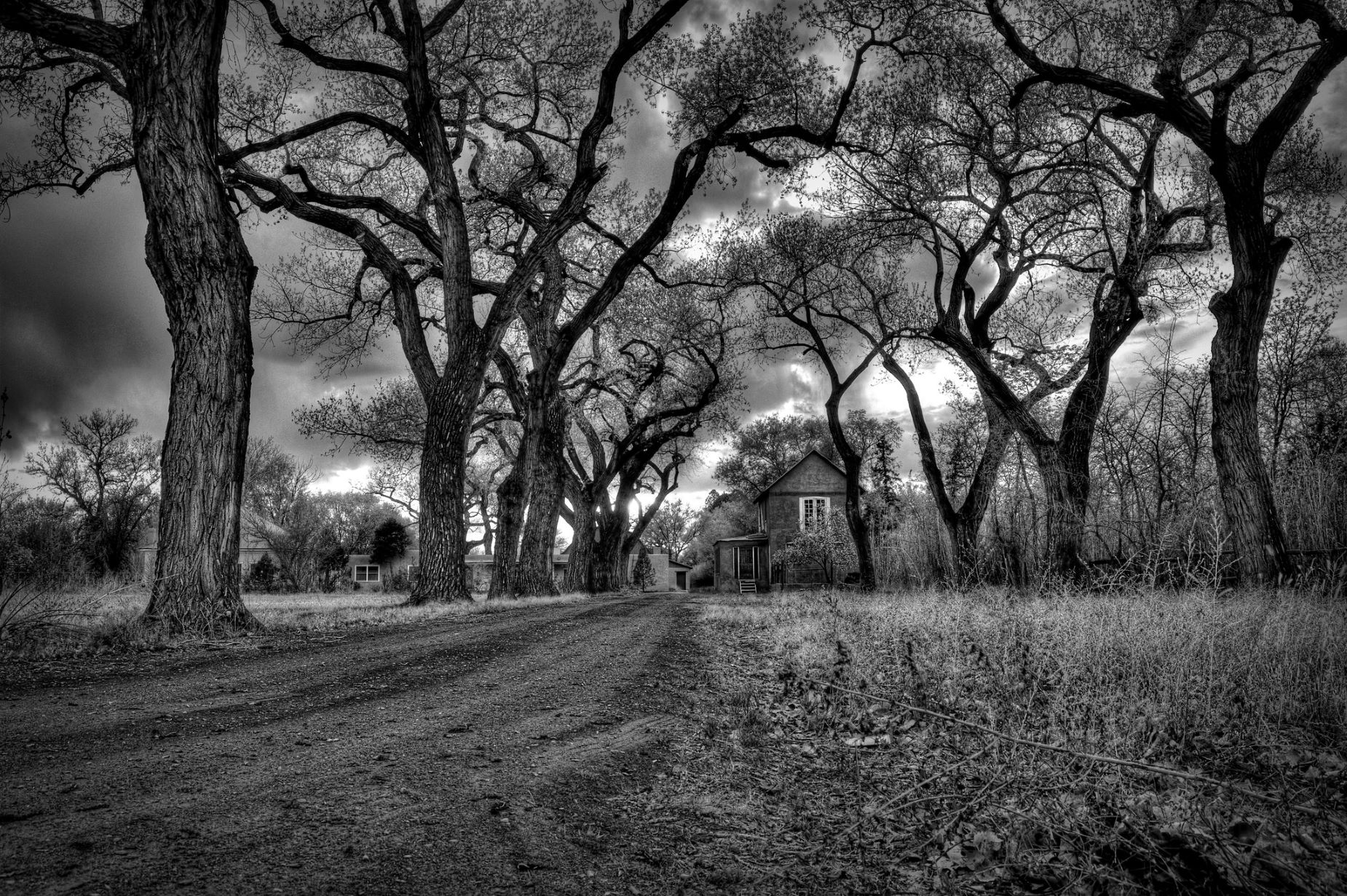

Back in the late thirties, a little before I was born, my father had a tenant house built. It was cleverly constructed—a boxcar partitioned into three rooms with windows, and a wash porch added onto one corner. The exterior was painted white, except for the window screens and front door screen, which all had green frames. Spirea bushes were set along the side that faced the road, and a huge mulberry tree was left to stand in the yard, which...