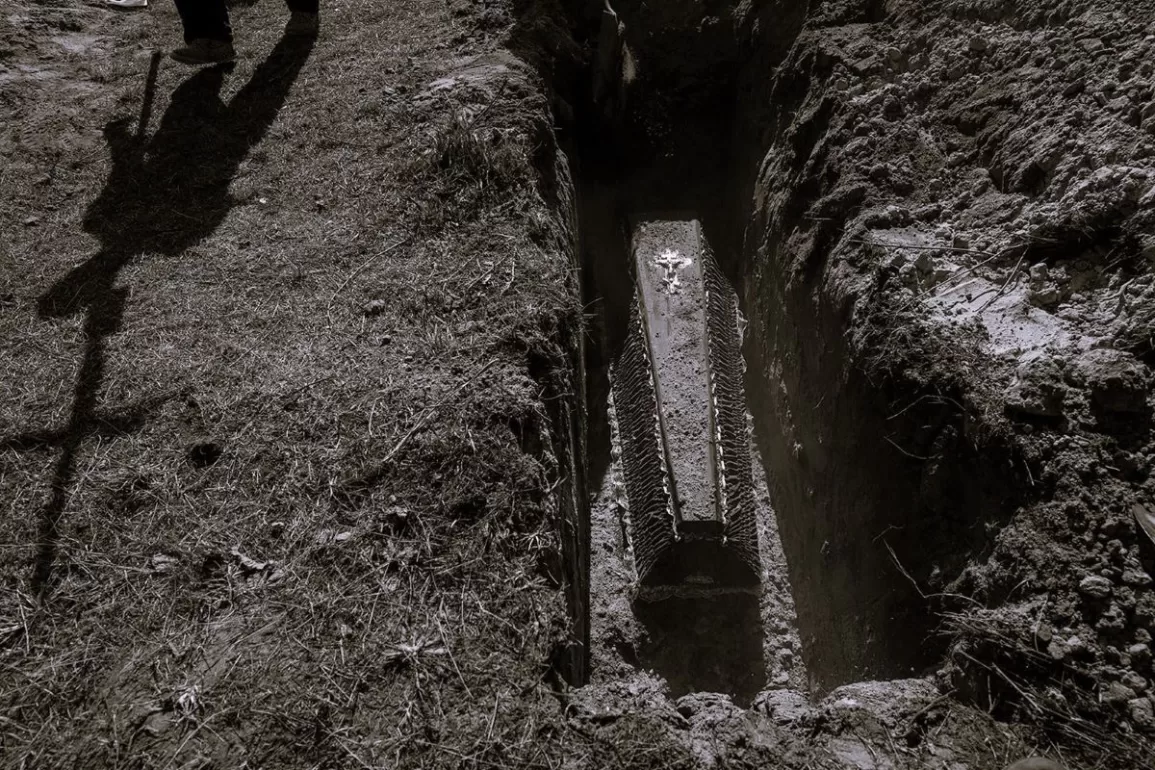

The day we buried Grandpa, the town flooded. Streams of rain rushed through streets carrying earth stolen from grain roots. We couldn’t hear the preacher’s sermon, and no one cared. Everyone was discussing whether or not the undertaker did a good job on Grandpa’s make up. Did he make him look livelier than when he was dying? They agreed about too much rouge on his cheeks to cover the yellow from the liver, but they loved his gray hair. Grandpa...