Despite being from a small Catholic country, the sheep of Ireland have garnered an international reputation for being particularly lustful.

Not long ago, millions of people on the Indian subcontinent picked up their newspapers to find a story about randy sheep that couldn’t stop breeding in Country Cork, Ireland. IANS, India’s largest independent news story, reported that a Pfizer plant in the village of Ringaskiddy accidently dumped millions of tons of Viagra into the harbor. As a result, IANS claimed that the sheep were in sexual overdrive and couldn’t be deterred by farmers.

The reporting was picked up by The Times of India, Outlook Magazine and Gulf News, and was the number one trending story in that part of the world, ultimately seen by tens of millions of readers. IANS was quoted as stating that “To the surprise of hundreds of shepherds, the animals behaved very strangely and were sexually overactive, according to a worldnewsdailyreport.com.”

The story persisted until one of India’s online news site, Altnews.In, did what the other sources failed to do: They visited the site of Word News Daily Report. If the outlandish headlines didn’t give them away, the disclaimer at the bottom noting that all their material was satirical should have made things clear.

The lesson here? Apparently nothing can be too absurd these days to be obviously in jest.

As an English major, I have always particularly despised the “winky face” and other emoticons. It felt like a degradation of language that wasn’t needed. Why devalue our great writers throughout history and the work they have done with the words we share by putting pictures of lips to say “thanks” or stick figures dancing to show that we’re happy? Why learn proper grammar at all? Nonetheless, in what has become a post-irony culture cultivated by the internet, some are arguing that the winky face is now very much necessary.

In 2017, Wired Magazine posted an article suggesting that Poe’s Law was that year’s most important phenomenon. Poe’s Law, originating from someone who identified himself as Nathan Poe in an online Christian forum in 2005, states that without a blatant indicator of the author’s intent, it is not possible to create a viewpoint so obviously hyperbolic and farfetched that someone won’t sincerely believe it online. In other words, if you say that it’s going to rain marshmallows tomorrow and don’t include a “😉,” someone, somewhere is going to buy Graham crackers.

Satire, nonetheless, is as old as the Greeks, and regardless of the internet, has been used to both humorous and political effect for millennia—even in agriculture. The Onion, which has fooled more than a handful of international public figures in its day, occasionally hits farming topics. In 2010 it reported that US congress accidently passed a $30 trillion soybean subsidy and as a result entire towns were buried beneath actual soybeans. Organic Times, a publication opposing GMO corporations, uses Onion-like humor to get their message across. The fast food chain Chipotle made controversial headlines in 2014 when they released their four-part Hulu series “Farmed and Dangerous,” which was meant to parody industrial agriculture.

The French, arguable the most ardent practitioners of satire, took to the form again in 2017 to criticize the Indian government. Cows are sacred in Hinduism, the most-practiced religion in India. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has largely been deemed a religious fundamentalist and accused of stoking hatred towards Muslims, Christians, and those with other beliefs. Although the Supreme Court of India reversed a ban on cattle slaughtering that was imposed by Modi, Modi has been denounced for encouraging vigilantes to attack and sometimes kill those transporting cattle to butchers. To protest this type of persecution, French journalist and author William De Tamaris made a 30-page cartoon series called “Sacred Cow” to suggest that India is no longer the peaceful nation devoted to Gandhi’s teachings that we still imagine it to be.

The classic Greek and Roman works of Varro’s De Re Rustics, Virgil’s Georgics, and Xenophon’s Oeconomicus mixed farming and political satire to establish principles of democracy, relationships, and morality that society still uses today. Thousands of years later, farming and satire are still used in union for both humor and politics. We may have a bit of work to do in figuring out which, as sometimes the breadth of the internet is larger than mankind’s common sense. Still, if farming and satire have survived this long, perhaps they will be part of the human experience that outlasts any other changes it may see in the future.

Until then, expect Irish sheep exports to increase. 😉

This article is part of The Milk House Column series, published in print across three countries and two languages. It can also be found at themilkhouse.org.

This article appeared in a similar form in Progressive Dairyman.

*

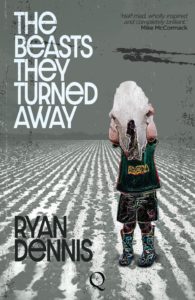

Ryan Dennis is the author of the novel The Beasts They Turned Away, available now for pre-order here.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.