This summer, people in New York State had something to talk about other than the wet weather. Convicted killers David Sweat and Richard Matt escaped from the Clinton Correctional Facility near the Adirondack Mountains, kindly leaving a note that read “Have a nice day.” For most of June the authorities scoured the state and looked into the background of the men for any possible clues. At one point they were thought to be spotted 20 miles from our house in Friendship, NY. It turned out to be a false lead, and although it cost the states thousands of dollars in helicopter fuel and manpower, it gave the area a brief thrill.

Western New York is no stranger to escaped convicts. In April 2006, Ralph “Bucky” Phillips escaped the Eerie County Correctional Facility by using a can opener to cut through the corrugated tin roof of the kitchen. He would allude police for the next four months, his reward reaching $450,000. He was placed on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list a day before his capture.

Although reports still remain in conflict, the story that local residents had heard was this: he was supposed to be in jail for 60 days for a parole violation, but a correctional officer lied to him and said he would be incarcerated for 6 years. The New York Times reported that Bucky was in the process of turning himself around, wanting to build a relationship with his daughter and grandchild. His family said that the husband of his ex-girlfriend had lied to Bucky’s parole officer in order to return him to jail. After his escape he spent the summer in the woods of western New York.

The most interesting part of the story were the reactions by local residents. A feverish buzz fell over all of us. We walked to the barn knowing that Bucky could be in the hedgerow at that very moment, watching our every move. We looked into distant tree-lines and became overtaken with the certitude that Bucky was somewhere inside there. We would excitedly talk about these feelings with others and confirm that they had them too. “I’d give Bucky a ride if I saw him,” one man would say at a family reunion. “I would too,” said another. Suddenly, the type of news that only seemed to happen in faraway places was right in our backyard.

Bucky Phillips eventually reached folk hero status. At the country fair that summer every tenth person wore a shirt that read “Run Bucky Run.” Others included “Where’s Bucky?”, “Got Bucky?” or “Don’t Shoot, Not Bucky.” A restaurant created the “Bucky Burger,” in a convenient to-go box for those “on the run.”

It may seem baffling why the region would side with a dangerous escaped convict that was loose in their area. The reasons are likely varied and complex. There was initial sympathy tied to the rumors that it was the lie by a guard that caused him to breakout when he would have been free in 60 days anyway. Many resident in faraway states do not realize how rural New York State is, and as such some locals did not like “the outsiders” (FBI and New York State Police) interfering with their everyday lives or invading their area. Some reported that the police cut their horse fences to drive ATVs without their permission, garnering hostility. Anti-authority feelings reached their peak in June, when police stopped Brad Horten on his four-wheeler for questioning. When he sped away a police officer fired eleven rounds in his back. Friends of Horton said that they were not allowed to find him to offer medical assistance as he lay dying. The officer claimed he was dragged by the ATV for a mile, but the evidence suggested otherwise.

Western New York is also an economically-depressed region. It has its fill of people who may at times feel beaten down or taken advantage of, even if the reasons and circumstances vary. In Bucky we saw a man besting the system. A local folk singer, in his song “Run Bucky Run,” had the line “It’s harvest time and my crops are rotting in the field. I ain’t done nothing wrong—Bucky I know just how you feel.” The fact that Phillips had spent 20 of his last 23 years in jail for various types of theft mattered less than the fact that “The Man” couldn’t get his hands on him.

Unfortunately, the story of Bucky Phillips ends neither neatly nor happily. They were reports that police were harassing his family, sometimes violently, which some say filled Bucky with rage. He evaded capture several times, but once shot three police officers. One of them ruptured an artery in his leg and died after amputation failed to save his life. Having then killed a man, Phillip’s hero status was over. He was eventually captured in a Pennsylvania woods, walking out with his hands up and an allegedly “defeated look” on his face.

The tragedy in losing two human lives should not be minimized, nor is it suggested that Bucky Phillips was a good man and that the cops were bad. Still, in the background of all the drama of 2006 was the story of us, the people of western New York. The rise and fall of Bucky Phillips took center stage, but that summer was also about who we were, the way we thought, and the way we lived. Going back now, one could see our dim reflection in the local newspapers and the conversations we had. We wanted something bigger than our ordinary lives, maybe even a hero. We wanted one of our own to beat the system, even if that meant adopting a convict, and if what the system was for each of us was left undefined.

“When all our crops are in the barn we know our work is done,” says the song. “Until then we’re with you all the way, so run Bucky run.”

This article is part of The Milk House column series, published in print across four countries and two languages. It can also be found at themilkhouse.org.

This article appeared in a similar form in Progressive Dairyman.

*

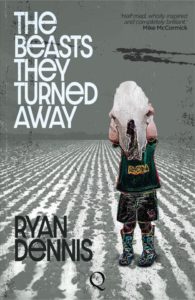

Ryan Dennis is the author of the novel The Beasts They Turned Away, available in North America and worldwide.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.