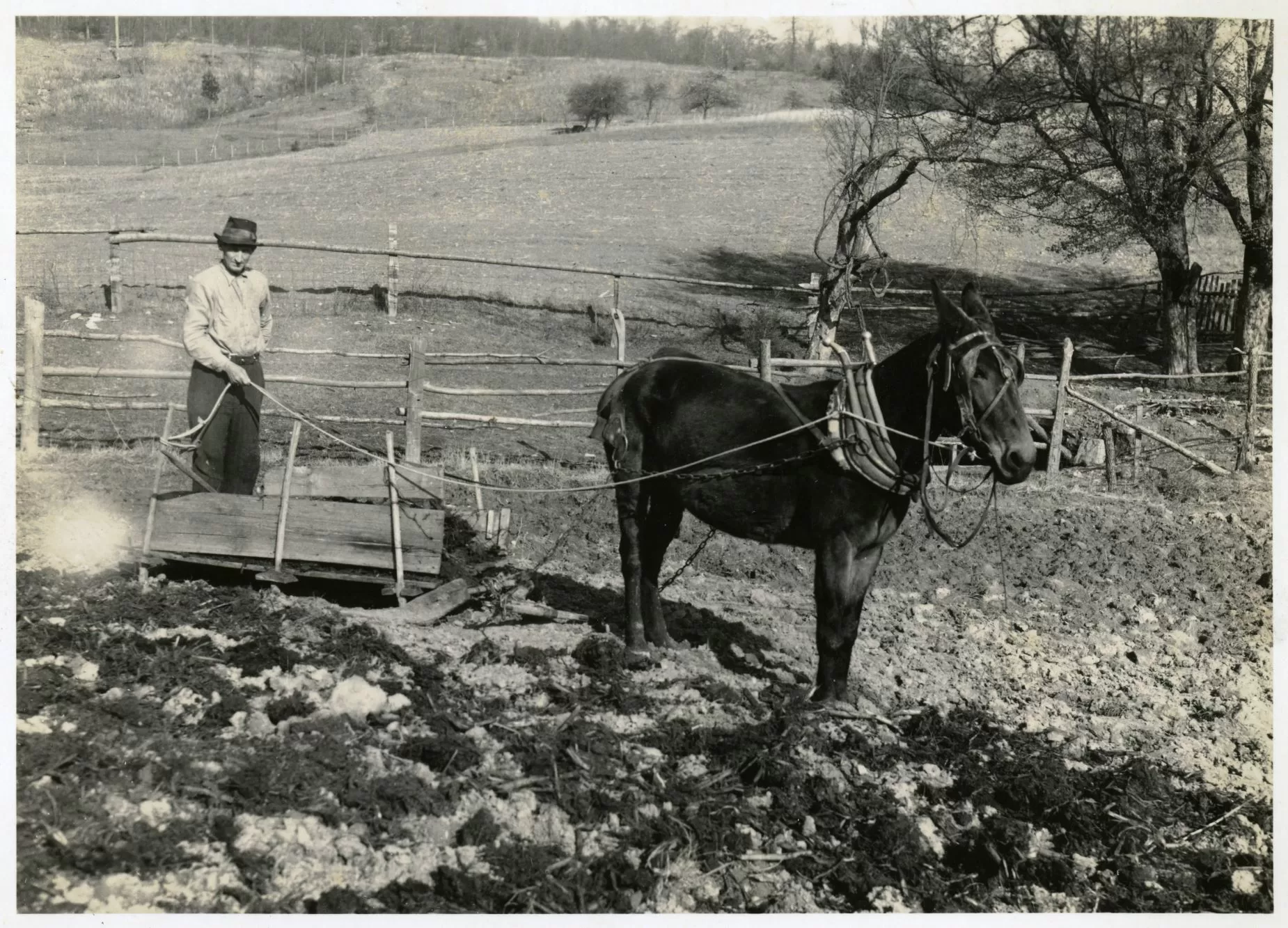

The early 1970s found us almost completely mechanized on our farm in the rolling hills of central Mississippi. At the end of another long, hot summer day, we typically came rolling in on our tractors, tired and dirty, but still filled with a sense of accomplishment after working fields for the last ten or twelve hours or more. Farming produces that feeling with surprising regularity, perhaps more so than any other profession. It’s not a Monday through Friday occupation; never...