Let us take a moment to appreciate just how versatile the cow is. We drink her milk and eat her meat. We can judge her, show her, and tip her over. With a bit of spray paint we can play Cow Chip Bingo for a laugh at the county fair. She’s the animal that our families have staked a living on, sometimes for generations. She can be a friend, a confidant, or a plain nuisance.

In southern Italy there’s one more thing she can do: intimidate.

Cattle are one of the oldest weapons used by the mafia to subdue local inhabitants. In addition to drug trafficking, prostitution and arms dealing, the ruling crime syndicates “tax” local businesses for “protection.” Farming is not exempt. In mafia-heavy regions such as Sicily and Calabria farmers are often obliged to pay monthly extortion fees. Those who don’t are likely to find a herd of cattle running through their fields, destroying crops and wreaking havoc.

Sometimes the mafia has an interest in buying farmland, if only to receive the annual subsidy grants from the European Union that marginalized land is sometimes awarded. Those who aren’t willing to sell are harassed by loose cattle or may find some their livestock decapitated and left on their doorstep. The mafia will continue to destroy a farmer’s crops until he is forced to go out of business, at which point the crime organization purchases it cheaply. This is especially true of the Sicilian Island, as the regional and infamous mob Cosa Nostra has partly been driven back into the countryside following a wave of recent arrests.

In some areas, such as Calabria, wild cattle herds have developed from the cows the mafia have let out. They, too, plunder local wheat and barley fields, sometimes attacking vehicles or people. These animals are called the “mafia’s sacred cows,” as they are meant to remind people of the control the mob has over the region. In 2005, a farmer complained to the authorities about a feral herd that was destroying his land. He was subsequently shot and killed.

In America, the mafia is the stuff of movies. The recent killing of Gambino boss Frank Cali this year suggests that the Five Families in New York City are yet active, but still we’re more likely to think of Pacino or De Niro being “wiseguys” in films like The Goodfellas, Scarface or The Godfather trilogy. Nonetheless, in southern Italy the mafia is the reality of everyday life. Since the 1500s, organized crime has taken root in southern Italy, currently with five major families controlling the area. From politics to the police force to legitimate businesses, there is nothing that the mafia isn’t involved in.

From the outside it may seem perplexing how a modern European nation can have half of it beholden to crime organizations. While the reasons are complex, it largely starts in the economics of the country. The south has always had much fewer occupational prospects than the north. In many areas, the only jobs available are those offered by the mafia. Meanwhile, long-term occupation by the mob has kept the south poor, further consolidating the mafia’s power. As some citizens point out, the mafia doesn’t kill randomly, but only when it profits them. In some ways they bring a sense of order, as they tamp down local thuggery and smaller criminality.

The mafia makes it entirely clear that it does not pay to oppose them. In many cases, a herd of cattle running across your field is getting off pretty light. My girlfriend’s second cousin worked as a lawyer for the Sacra Corona Unita mob in Apulia. His job was to “clean” some of the laundered money the organization obtained by illegal ventures. Apparently he attempted to keep some of that money for himself, because he was found shot to death and burned in his car.

In the past, those with better intentions who tried to stand up to organized crime in Italy also didn’t fare well. Governors, police chiefs, political leaders, trade unionists and journalist fill the lists of those murdered by the mafia in the last handful of decades. Most famously, anti-mob prosecutor Giovanni Falcone and his wife were killed in a car explosion in 1992. His colleague, Paolo Borsellino, suffered the same fate a few months later. Today, few Italian politicians in the south openly oppose the mob.

These last few years, however, have seen an increase in the number of mafia-related arrests. Last year 84 members of the ‘Ndrangheta family were caught, and Cosa Nostra had one of its bosses and 45 of its constituents taken in by Sicily’s anti-mafia unit. In part, this suggests there’s more of an appetite for going after the mob, although in many cases it includes other countries into which a crime organization was seeking to extend business. In Calabria a group is starting to round up the wild cattle, after local citizens have formed the organization for that purpose. The lawyer that is heading the effort has had his car gored by a bull, but as far as what can be found on the internet, is still alive. Nonetheless, there’s a long way to go before farmers and the rest of southern Italy can free themselves of the mafia’s oppression.

This article is part of The Milk House Column series, published in print across three countries and two languages. It can also be found at themilkhouse.org.

This article appeared in a similar form in Progressive Dairyman.

*

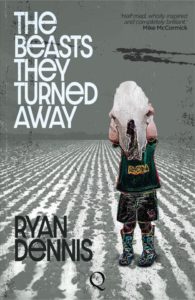

Ryan Dennis is the author of the novel The Beasts They Turned Away, available now for pre-order here.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.