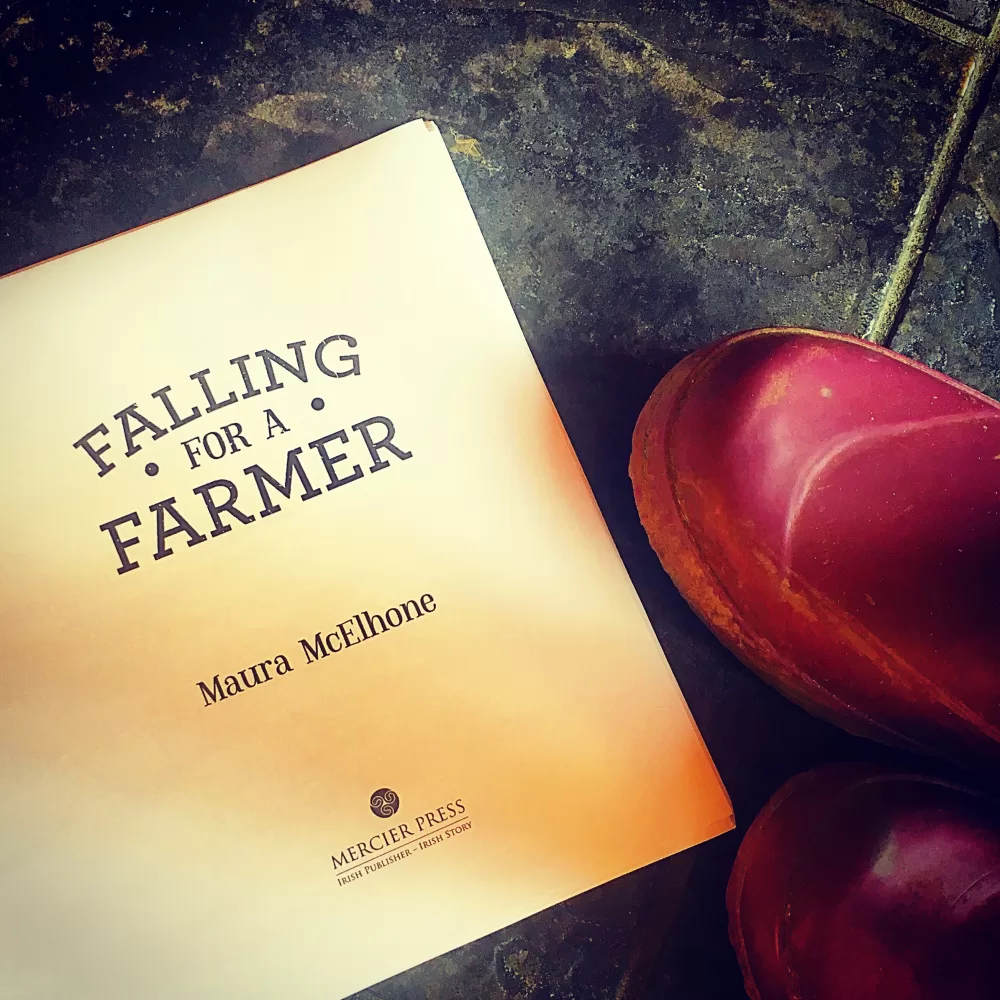

The following is an excerpt from Irish writer Maura McElhone’s book Falling for a Farmer (2018), published by Mercier Press. * It was, if you’ll excuse the terrible pun, the tail end of calving season, a term that I’ll admit was alien to me before meeting Jack. When he introduced me to the phrase, powered by innocence and naiveté, my mind simply conjured up images of adorable baby animals taking their first wobbly steps in this world. I knew nothing of the...