“It’s all the rage,” my father said. “Everyone is doing it.”

I was a bit skeptical. The last time my father told me about the latest rage that everyone was doing he has referring to “finger trolling,” where you apparently tie nylon line to your finger and try to fish off a dock. It turned out, finger trolling was part of a joke advertisement by Old Spice, and no one was doing it.

“Cornhole,” my father insisted. “It’s sweeping the nation.”

My girlfriend, Alessandra, and I had to end our South American trip early due to the pandemic and shelter at my parents’ farm for several months. It’s never easy bringing a girl back home, even with both of us in our thirties. Everyone tried to be on their best behavior to make the temporary living arrangement work. Since she is from a city in southern Italy, I did my best to prepare her for American rural culture and explain the things she might not understand. When my father rushed out to meet the UPS man and nearly hugged him after getting handed the cornhole set, I told her: “Grown men throw beanbags at a wooden box. It’s all the rage I guess.”

It soon became apparent how much life in the American countryside had changed since I had left to live in Ireland. The first get-together, once it was admissible to meet in small groups after the lockdown, was a cornhole tournament organized by my father’s friend. After we arrived, the small talk didn’t last long before we were asked to draw numbers out of a hat to settle teams. It was obvious that cornhole wasn’t a side activity enhancing the opportunity to get to enjoy each other’s company again. Instead, cornhole was the main event.

There’s something dangerous in giving middle-aged men a “sport” to play. Suddenly, that athletic spirit wells up in them that they haven’t felt since high school basketball. They’re yelling “Yes!” when they land a beanbag on the board and curse under their breath when they don’t. They shout at their partners or wives: “Come on, Baby, you got this.”

One thing I learned recently is this: It is inherently awkward to see a man over fifty pump his fist in the air.

That was, by no means, the last cornhole tournament, nor the only house we went to in order to play. Picnics, birthdays and anniversaries were pushed aside during the pandemic, but cornhole was played this summer. Often, when a team wasn’t in a match they sat nearby and said things like, “Doesn’t that one board feel a bit slippery to you? Do you think the angle is correct per regulation?” Once, I recorded a complete game on my phone, thinking that when everyone comes to their senses again historians will want to have this dark moment in our history documented.

One evening, Alessandra suggested that, to spend time with my parents and come to terms with their new lifestyle, we play them in a game of cornhole. In that way, she proposed, maybe we could begin to understand them again. To me, it seemed like walking into the lion’s den with steak hanging out of our pockets. However, I knew that she wanted to be a good guest with my parents, so I eventually gave in.

Before the first bag was thrown someone suggested that we make the game interesting. “Impossible,” I muttered, even though I knew they meant betting. I suggested that our dignity was already at stake by just being out here, but everyone was too revved up to pay any heed. In our family no one is really comfortable taking money from each other, nor would it constitute a meaningful enough award. Instead, we decided to get serious: The losers had to feed the chickens afterwards.

As my parents tried to find an even place in the lawn and make sure the boards were 27 feet apart, I leaned towards Alessandra and asked if she really wanted to do this. Before I knew it, however, the bags had started flying.

The thing about Alessandra is that she is both competitive and hates being competitive. She would work hard at becoming the chip leader in a poker game and then go all-in with a 2 and a 7. The two sides of her personality are always at odds and can be seen struggling with each other by those who know to look for it. She surprised us all by sinking two bags in a row into the box. The next one she threw without aiming. It went sideways across the lawn and almost hit the dog. She looked at me and shrugged.

Another thing about my family is that we’re bad at remembering numbers. My parents hadn’t gotten around to creating a tallying board, and after every round the score was in contention. Meanwhile, Alessandra has an unhuman ability to remember facts and figures, but chose to remain quiet. Politeness, I guess.

The lead that Alessandra and I had started with evaporated when my mother put one in the hole and my father left three on the board, quickly gathering points. They now had a one-point lead, with both scores close to the 21 needed to win. It was getting louder as the tension built. We ribbed each other, saying expected things like “You might as well start doing the chicken chores now,” or “You’re going to choke under so much pressure, might as well give up.”

Suddenly, Alessandra sank the bean bag into the hole. “F@%k the chickens,” she said.

We haven’t played since.

It has been difficult for me to come to terms with the America that I’ve come back to. I remember the day when we all got upset finding bowling on ESPN, and now it’s cornhole—and the people playing aren’t even good. Worse, five different people have told me that they watched it on television. At least horseshoe players knew to stay in their lane.

Back in Ireland, I was with friends at a two-day softball tournament. The first night all the teams gathered together to get to know each other. I was looking forward to socializing the way I had known before: sharing jokes, rumors, and half-truths, and getting full of ourselves. If anyone knew how to do this, it was the Irish. I was looking forward to a good old-fashioned night of rabblerousing, safe from beanbags and wooden boxes.

Suddenly, the crowd parted and a man my age came through carrying a large package. “Hey Lads, look at this game I got off the internet. It’s called cornhole.”

This article is part of The Milk House Column series, published in print across three countries and two languages. It can also be found at themilkhouse.org.

This article appeared in a similar form in Progressive Dairyman and Farm and Livestock Directory.

*

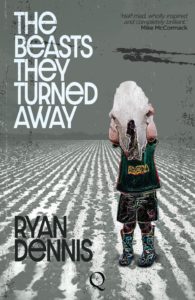

Ryan Dennis is the author of the novel The Beasts They Turned Away, available now.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.