I have a feeling that most people are going to remember the moment when they realized that the Coronavirus was a real threat. For me, it was when it prevented me from getting to see colorfully dressed women body slam each other to the ground.

My girlfriend and I were on our once-in-a-lifetime trip through South America before settling down into the routine of normal work-life (not knowing at the time how absurd the term “normal” would become in 2020). She sometimes criticized me for not deciding on something specific that I wanted to see or do Apparently my go-to line of “I’m in good company, so why do I care?” got tired. Hence, to demonstrate my assertiveness, I made my stand in La Paz, Bolivia: I wanted to see Cholitas wrestling.

In Bolivia, the rate of domestic violence was particularly high, especially among the indigenous Aymara population. Victims began meeting together to learn how to perform staged wrestling moves as an innovative way to release anger and make friends with similar experiences. They learned acrobatic maneuvers and stunts in a performed “battle” against male oppressors. Like in most countries, staged wrestling by men had already existed in Bolivia for a long time. However, in the early 2000s promotor Juan Mamami saw the commercial value in Cholitas wrestling and convinced the women to perform the act professionally. Cholitas wrestling soon became a phenomenon in La Paz, gathering large crowds of both Bolivians and tourists every Sunday night.

Growing up in the nineties, I was aware that many of my classmates were into pro wrestling. I heard of people like Stone Cold Steve Austin and The Undertaker, and knew that the full nelson was some sort of take down move—but that was about it. (And, I could recognize Hulk Hogan, but mostly from some of the movies he did…which, let’s be honest, haven’t aged well.) The thing that I didn’t understand was that even though it was obviously fake, no one seemed to admit it. Some kids got together and watched it like it was a real sport and talked about it the whole next day.

It turns out, there’s a specific word in the staged wrestling industry to denote its open secret of being scripted: kayfabe. Like the fourth wall in acting, kayfabe is the idea of staying in character, as if the wrestling personalities are real people. For decades kayfabe was maintained in pro wrestling, suggesting that the feuds, grudges, and relationships between wrestlers were simply reality. (In fact, the first public acknowledgment that wrestling was fake didn’t come until a governmental hearing until 1989, and that was just to avoid paying the taxes put onto actual sporting events.) It wasn’t until the advent of the internet that the facade began to thin away, and wrestlers were often caught out of character in their real lives.

The nineties were the apex of pro wrestling in the United States. Terms like “WrestleMania,” “WWF,” and “Monday Night Raw,” are familiar to me after all these years, even though it is only now, looking them up, do I really know their context. However, for better or worse, pro wrestling in the US has been in a steady decline for a while. It seems that in the time of a quickly advancing entertainment industry with the likes of Netflix and sports streaming, there are fewer people willing to turn back the clock and suspend their disbelief for a good old-fashion throwdown. Bolivia was going to be my last chance to live a part of my childhood that I hadn’t experienced before.

The cost of the ticket to see Cholitas wrestling was $13, and included a taxi, entrance, and nachos in the arena. I prepared myself by watching video clips, since the wrestlers are known to interact with the crowd—usually trying to kiss members of the audience or throw drinks at them. The indigenous women of Bolivia all wore the traditional colorful dresses (polleras), black bowler hats, and long braided hair—and were nearly always quite hefty. Seeing these women piledrive masked men and then each other was going to change my life in ways I would never be able to fully articulate.

Instead, I’m still the same man.

The wrestling, of course, it didn’t happen. The show got cancelled and our tickets refunded. It turned out this Covid business was getting serious. And, despite how unique and culturally rich time spent in Bolivia can be, it is also synonymous with nonstop diarrhea. We knew he had to leave the country before getting stuck there for longer than our bodies could hold up.

Having to miss out on the Cholitas ultimately paled in comparison to the inconveniences and difficulties brought about by Covid 19. Still, for me it will always mark the innocent and naïve beginning of the pandemic…as well as a growing and unhealthy obsession with wanting to see middle-aged women powerbomb each other to the floor.

This article is part of The Milk House Column series, published in print across three countries and two languages. It can also be found at themilkhouse.org.

This article appeared in a similar form in Progressive Dairyman.

*

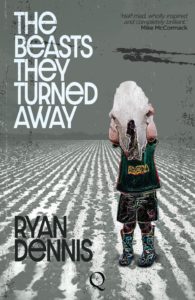

Ryan Dennis is the author of the novel The Beasts They Turned Away, available now for pre-order here.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.

Íosac Mulgannon is a man called to stand.